Is the federal government injecting new money into the economy? Maybe not

Commercial banks create the overwhelming share of the money floating around in the economy. But recently, attention has turned toward the federal government and its capacity to create deposit money in collaboration with the Bank of Canada (which the ministry of finance owns). The worry is about inflation.

In the first two quarters of this year, the federal government added over $200 billion to the federal debt by spending money on expensive social programs, bringing in less tax revenue, and issuing a large assortment of securities (in the form of treasuries and bonds). Folks are beginning to ask: how much of this debt was financed by the Bank of Canada using the "printing press"? The worry is that there's only slightly over $2 trillion CAD worth of deposits in the Canadian economy, and so if the government printed anywhere near $200 billion CAD we might need to start thinking about inflation.

We've spent some time crunching numbers, and what we've found is that the federal government may not have injected that much new money into the economy over the last 6 months at all. In fact, it looks like they've spent a ton of existing money while also stockpiling it at the Bank of Canada.

ADVERTISEMENT - ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW

How the federal government can create new deposit money

Commercial banks create new deposit money through their accounting practices when they issue loans to customers. They create an asset (loan contract) and liability (deposit) of equal value when a loan contract is signed by a borrower. No existing money is transferred to the borrower in this process. That's why it's called money creation. If you look at banking statistics, you'll notice that there are approximately the same amount of deposits as there are credits in the banking system.

The federal government doesn't borrow much money from commercial banks these days, but it regularly does through the Bank of Canada - the official banker of the Government of Canada. This happens when the Bank of Canada purchases securities in the form of treasuries and/or bonds directly from the government. When these transactions occur, the Bank of Canada ends up holding an asset (created by the federal government) and simultaneously a liability (which it creates out of nothing) of equal value in the form of a central bank deposit (also known as a "reserve"). The central bank is left holding an asset which earns it an interest, while the government ends up holding central bank reserves (equal to bank deposits) which it can then spend by transferring balances to accounts with commercial banks. The deposits created in this process are not transferred from somewhere else by the Bank of Canada; they are newly created.

This type of transaction occurs on a regular basis. The Bank of Canada practices a number of "balance sheet management" strategies which involve purchasing securities on a regular basis and depositing newly created money in the government's bank account. This bank account can see huge flows of money, so it is important that the account never hits insufficient funds.

How can we track this newly created money?

In theory, if the Bank of Canada continuously finances the government in this way, it could result in a lot of new deposit money being created and injected into the economy. That is, as long as the newly created deposits leave the Government of Canada account at the Bank of Canada, all while the Bank of Canada's stockpile of outstanding government securities it acquired directly from the government continues to grow.

In order to find out, we examined monthly statistics published by the Bank of Canada, drawing on available statistics for assets and liabilities held by the central bank, including how many government securities and deposits belonging to the federal government are held by the institution.

One of the problems you immediately run into is identifying how many government securities held by the Bank of Canada were directly purchased from the government (they don't tell you). Most of the central bank's purchases of government securities are in the secondary market, which leads to cash or deposits being created for (and held by) non-government entities, like banks. So, we had to filter out the securities which were likely bought by the central bank each month from non-government entities in exchange for deposits or cash. Repo agreements (assets on the central bank's balance sheet) are also part of the equation and need to be considered. When it was all said and done, we ended up with a figure for residual securities held by the Bank of Canada, or an estimated number of securities likely purchased directly from the federal government.

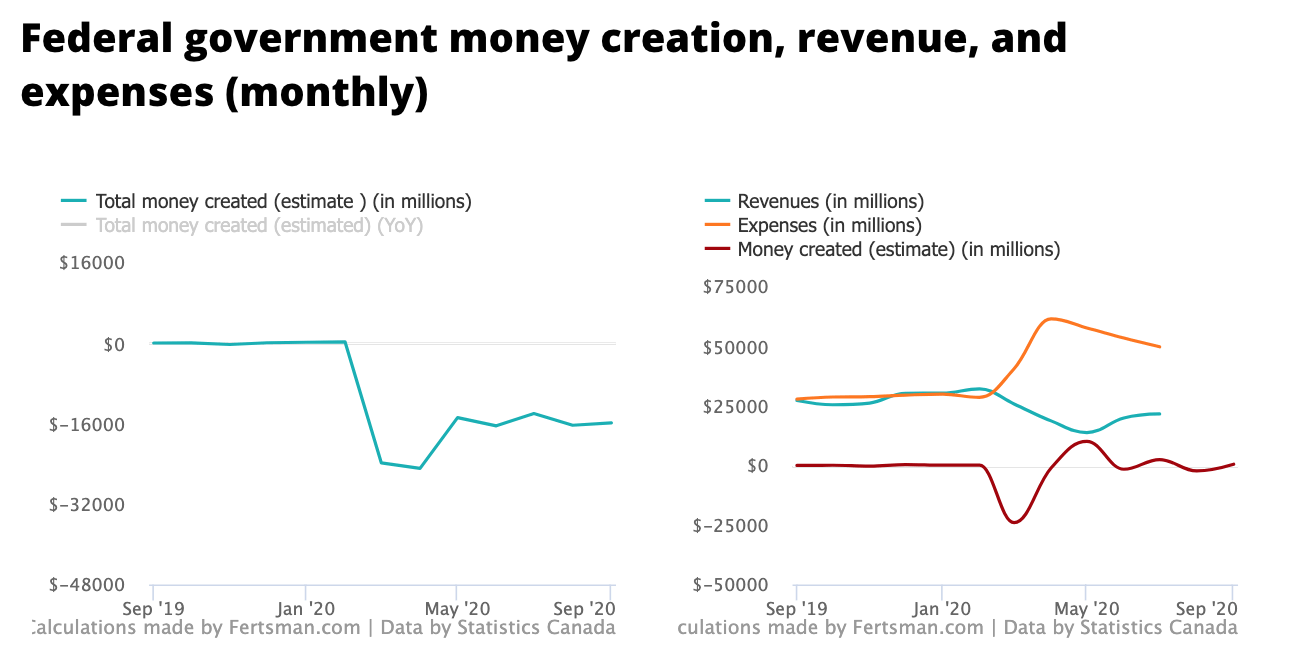

To figure out how much money the government has injected into the economy, we took this figure for the estimated number of securities held by the Bank of Canada likely purchased directly from the federal government less the figure for total Government of Canada deposit held at the central bank. If the figure is positive, there are more securities outstanding than deposits held, which in theory could mean that deposits have been injected into the economy by the government. If the figure is negative, there are fewer securities outstanding than deposits held, which in theory could mean that deposits are being removed from the economy and are being stockpiled by the government.

ADVERTISEMENT - ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW

Caution: the money created indicator is experimental

As you can see from the charts above, what we've found is that there is actually way more deposits in the government's account at the Bank of Canada than outstanding surplus securities since March of this year (when the pandemic hit). There was about $23 billion CAD more deposits than surplus securities in March, and over $15 billion CAD more deposits than surplus securities in September.

Despite a huge jump in expenses and a huge slump in revenues beginning in March, it does not appear that the government has injected new deposit money into the economy. To the contrary, if the estimates are correct, it seems that the federal government has been stockpiling deposits at the Bank of Canada.

We heard that the Bank of Canada has purchased a huge amount of outstanding government securities, ranging somewhere in the $240 billion CAD range. It's true, the Bank of Canada was holding about $100 billion CAD worth of bonds and treasuries at the beginning of the year. But, as of September, the balance is about $344 billion CAD.

That being said, the majority of this balance was purchased in the secondary market, resulting in a lot of deposits being created for members of Payments Canada like banks. In fact, there were over $337 billion CAD worth of deposits held by these members in September, up from $250 million CAD at the beginning of the year. Meanwhile, the government is holding just over $81 billion CAD, up from about $25 billion CAD at the beginning of the year.

The bottom line is that it appears that the Government of Canada hasn't created and injected a bunch of new money into the economy at all, despite all the social spending and debt issuance. The government appears to be stockpiling deposits in excess of the amount of securities we believe were purchased directly from the government by the Bank of Canada. That means the government's huge spending has, at least to date, been financed by tax revenues and sales of securities to the secondary market: a source of existing money.

The inflationary doomsday prophecies of inflation are likely terribly overstated. Alas, we should be worried about deflation.

Cover image by Mick Haupt

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Enjoyed this article and want to support our work, but are using an ad blocker? Consider disabling your ad blocker for this website and/or tip a few satoshi to the address below. Your support is greatly appreciated.