Why banks chasing profits can be bad for the economy: the case of US farm credit. Where's Trump?

July 12, 2019

Erik Fertsman

The large banks in the US have shifted away from lending to farmers. Now, these farmers are desperate for credit and higher commodity prices. This is a classic example of why banks should not be allowed to chase profits over everything: it's bad for the economy, and it's bad for the banks themselves.

Yesterday, Reuters

released an excellent piece on the state of financing for farmers in the United States. In short, US farmers are struggling with their businesses and large banks have been cutting them off from much-needed credit. The large banks are basically saying, "no credit or bailouts for you," rural farmers, who feed the nation and parts of the world...

My initial thoughts were: Thomas Jefferson is rolling over in his grave. Jefferson was a staunch supporter of rural Americans, and fought the good fight on behalf of its agrarian society. Importantly, he's at the center of many chapters in US banking history, wherein he played a pivotal role against national banking and a system that predated, but ultimately spawned, the Federal Reserve banking system.

Lending to farmers has been a key component for US banking entities since, at least, forever. But the aftermath of the Savings and Loans bust in the late 1980s is when agricultural lending brought farmers into the "everything bubble" realm. But of course, business for the banks in this sector has been decent for a while, especially when farmers were earning more money all during a time whereby their assets were increasing in value. These assets could be used as collateral for loans, which made bankers even more money.

Reuters wrote how JP Morgan Chase's agriculture balance sheet grew by 76 percent between 2008 and 2015. Since 2016, though, income among farmers has been falling, and the US-China trade war has, allegedly, prompted large banks to stop offering credit to farmers due to their unfortunate position. This is effectively becoming an access-to-credit issue now. Rather than continuing to support farmers, large banks are backing-out due to foreseeable risks. An appropriate strategy? Let's take a look.

Reuters wrote how JP Morgan Chase's agriculture balance sheet grew by 76 percent between 2008 and 2015. Since 2016, though, income among farmers has been falling, and the US-China trade war has, allegedly, prompted large banks to stop offering credit to farmers due to their unfortunate position. This is effectively becoming an access-to-credit issue now. Rather than continuing to support farmers, large banks are backing-out due to foreseeable risks. An appropriate strategy? Let's take a look.

What did the Reuters report say?

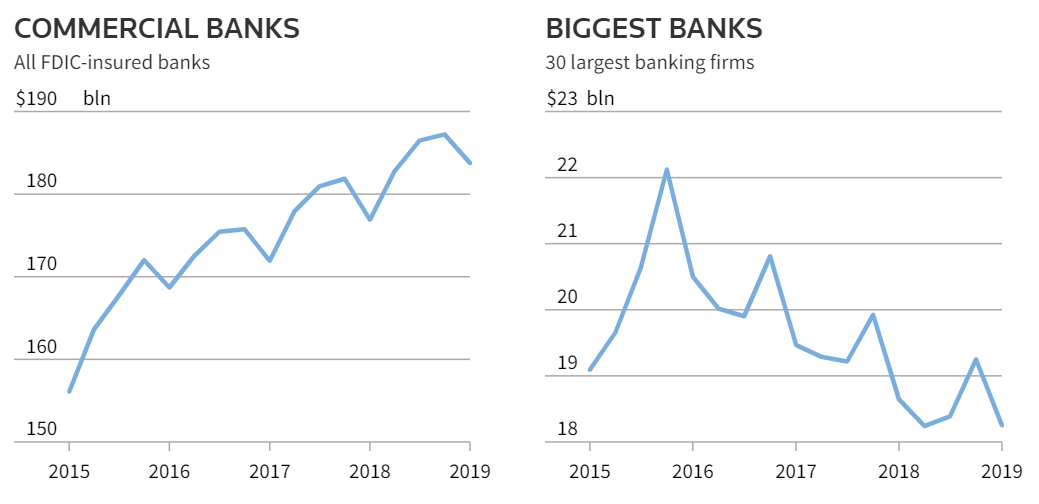

Using data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Reuters has confirmed a trend of declining asset (loan) quantities to farmers (17.5 percent decline, to be more precise). They point out how their report is one of the first to touch on the issue, and that it's coming out a bit too late, as farmers either retire early or are going bust as a result of the credit issue. Below you can see the info-graphic from the Reuters report.

The graphic shows the trend of total commercial bank credit to agriculture to the left, with the total bank credit issued to agriculture among the biggest banks to the right.

They cite how credit demand continues to expand, especially in the midwest and among grain and soybean producers. Reuters wrote how the lack of credit supply (they are talking quantities here, not interest rates) "can threaten a farm's survival, particularly in an era when farm incomes have been cut nearly in half since 2013."

Earlier this year, Reuters said FDIC-member banks reported a 100 percent increase in 90-day delinquencies. Moreover, delinquency rates have gone to 4 percent or more among the large banks (Bank of America, PNC Financial Services, etc.)!

JP Morgan responded to Reuters by agreeing with the findings, yet they also said that they had not, and have not, "strategically reduced" their exposure to farmers. What's more, JP Morgan said they have a wider definition of "agricultural assets," of which includes other food processors and companies as well as related businesses.

There's more data to add linking the situation to the economy

To say that the large banks have not "strategically reduced" their exposure to farmers would not be genuine if you have rising delinquencies and data showing a clear deviation between total lending to farmers between large and small banks. So, I'm not sold on JP Morgan's response. If fact, the data looks like something you would see in a market that is experiencing structural reforms.

While the Reuters report did a good job on specifics and reaching a broad audience, they didn't cover some of the more important data that can make for a better argument, while linking the problem to the actual economy.

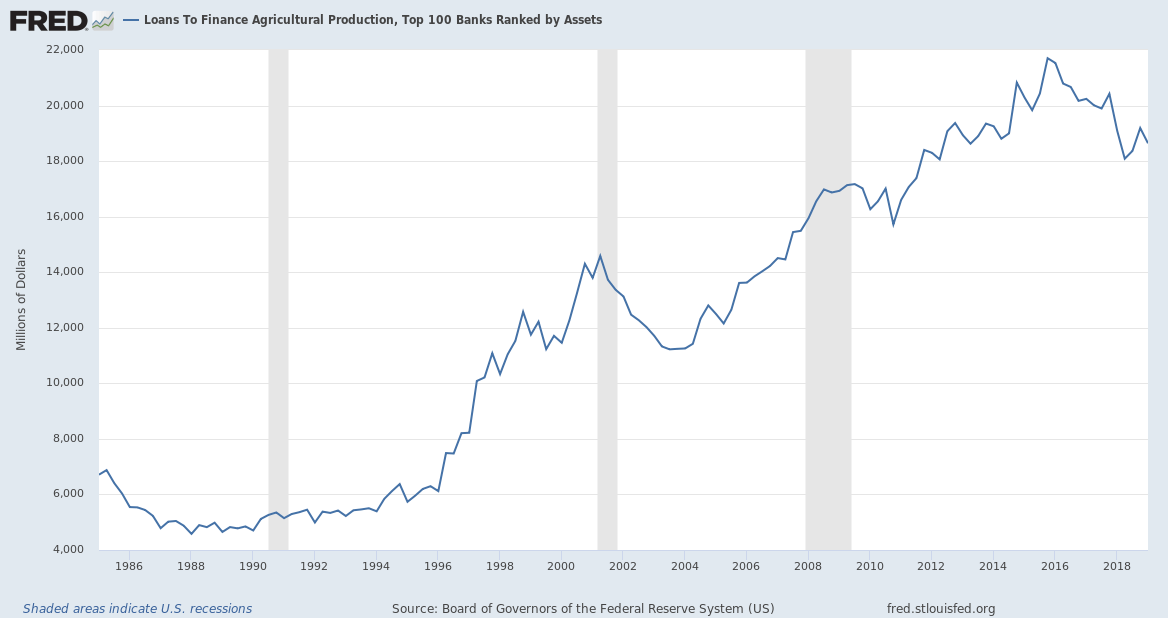

For starters, on the chart directly above, we see how credit to agriculture among the top 100 banks has declined with no prior recession (grey-shaded are on the chart). Previously, loan growth took a dive after a recession. We can also see how, since 2016, loan growth has changed its trajectory to the downside. The data is now trending downward. So, in short, to claim that there hasn't been a strategic shift in business among the top banks to the agricultural sector is strictly disingenuous.

Moreover, since lending decreased to the agricultural sector, we now see a rise in delinquency rates for the top banks. So the conscious effort to reduce exposure to farming, and so on, by the large banks, has left balance sheets reeling - with more risks still in store. When you shut off the credit spigot in a sector that is still growing with credit demand, and you don't really coordinate with the government, you and that sector are going to end up having some problems. Was this done on purpose? Maybe to build some leverage over the Trump administration, who came in around the same time credit was getting shut-off? I'm speculating at this point.

How does total agriculture credit compare to economic growth in the US? If we line-up total loans among the large banks against GDP in dollars (see chart above), then we begin to see the trend. At the moment, GDP does not seem to be flexing downward due to the slump in total agri-loans. So, it remains to be seen how, exactly, this credit slump will play-out in the rest of the economy. I couldn't find specific US farming data that I was looking for, but once I do I'll update in a new article.

Collateral damage: smaller and local banks

The exodus of the large banks from agricultural lending is wrecking havoc on smaller banks and lenders who are exposed to the sector (see chart above). As you can see, delinquency rates have shot-up for small lenders. In many places across the US, you have banks that have a substantial size of their balance sheet devoted specifically to farmers. Now that the large banks are gone, the credit spigot just got a lot smaller. This will have a deflationary impact on farm monies and prices that are used to service credits and post collateral.

Reuters reports how these smaller banks have gone to the US Department of Agriculture for help, leveraging programs that provide loan guarantees that cover up to 95 percent of the loans issued. These program were created with the 1980s farm credit crisis in view, which does, indeed, help local banks lend to farmers who are considered higher-risk.

There's a few things to note here: banking and government is heavily intertwined, as you can see. But only at the lower level. Without the collaboration, the banks would not be able to lend to farmers at costs both the farmers and banks can afford. Since farmers are higher-risk borrowers (just like poor segments of the population), the banks really should

be charging higher interest rates in order to cover costs from delinquencies and bankruptcies - which are pretty much guaranteed.

If you make the argument that government and banking collaboration created this mess in the first place, you miss a few vital points. Without the collaboration, farmers wouldn't exist. Or, at least, farming in the US would have a substantially smaller footprint. What's more, these banks wouldn't exist either. Nor would the big banks have allocated credit to the agricultural sector to make money for their shareholders.

In fact, I'd argue that you should have more government and bank collaboration, and add regulations to what the big banks can do in the sector. What the large banks have effectively done is pump the sector full of money, then all of a sudden, turn the pump off. This puts everyone in an awkward situation. Where's Trump when you need him? I thought he was fighting the good fight in the name of those rural townships?

All of this was exactly what Thomas Jefferson feared, and now it's become a reality once again. When will America learn that banking cannot be done in the name of profits over everything? Farmers, like the poor, are particularly vulnerable to the banking industry as it exists in its current form. It's high time for this problem to be acknowledged in a way that I have done here, wherein I wrote about issues with banking the poor.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Enjoyed this article and want to support our work, but are using an ad blocker? Consider disabling your ad blocker for this website and/or tip a few satoshi to the address below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

BTC Address: 13XtSgQmU633rJsN1gtMBkvDFLCEBnimJX