Stephen Poloz's bombshell confession about interest rates and what they don't do for the economy

July 11, 2019

Erik Fertsman

We've seen the Basel-based Bank for International Settlements come out and say that inflation-targeting policies aren't really working. Now, the Bank of Canada's chief, Stephen Poloz, has come out and said that it's "a little too easy" to believe lowering interest rates makes everything hunky dory.

If you've been following the state of Canadian monetary policy lately, then you probably know that the Bank of Canada (BoC) has been having a hell of a tough time dealing with anemic economic growth in Canada since 2008. Of course, a select few speculative assets (like housing) have experienced huge gains because of government and BoC policy. But these policies have benefited the country disproportionately. For example,

Ontario and BC have taken much of the home asset price inflation gains (and now losses). At the same time, many Canadian demographics are now more worse off than others due to high debt-to-income and/or high debt-to-asset ratios - just because they didn't catch to asset price inflation wave (I'm currently writing an in-depth piece about this).

Importantly, nominal GDP has been underperforming (when compared to the OECD average), the economy stalled in 2015, and then nearly again at the end of 2018. Now, debt levels among Canadian consumers have reached epic proportions. Asset inequalities between Canadians, especially millennials, have also gone into the stratosphere. The data is trending in an unfortunate direction, but the BoC seems to be doing little about it. Why?

The BoC is staring at the data

After reviewing Canadian and global data for the second quarter, the BoC came out yesterday

cursing

the global economy and the trade war, and blaming any poor-performance in the Canadian economy on things going on outside of the country. In response (the bank has to respond, right?), it decided to hold its key interest rates unchanged. This occurred despite the poor economic data coming in about the Canadian

economy, which I

highlighted here

just before the rate decision. I said they wouldn't cut rates at the moment, but they surely will when their inflation-targeting policy is at risk (namely, if the Canadian dollar strengthens too much), and when GDP data shows deterioration. If the US's Fed cuts, the BoC will automatically follow since both economies are super interlinked.

Ok, the bank didn't rush to respond by lowering rates yesterday... And in many ways it makes sense: the bank needs to wait for the GDP figures, first and foremost. When GDP data comes in for the second quarter at the end of the quarter, it's sketchy at best. Statistics Canada and other agencies that collect lots of the data used for the calculation will end up revising the data, sometimes as far out as a year later. So, it's very difficult for the BoC to put confidence into the data when it's fresh. Or, is there something else on the bank's mind?

Poloz's bombshell statement to reporters

Shortly after the rate decision announcement yesterday, a few very interesting things were said by the bank's chief to reporters. According to

Bloomberg, Stephen went on about how investors think that the central bank, through monetary policy, can somehow magically cure ailments caused by the trade war and global economic conditions by way of lower interest rates. In a somewhat perplexed fashion, he said that they need to understand the "complexity of it," and that, "it's not as easy as lowering borrowing costs." BOOM.

What does he mean? I don't think the BoC actually knows. All they can feel right now is that monetary policy (what they have been doing for the last 30-50 years) is not

working. That statement above should really be seen as a confession of this. It's a bombshell. My readers will know, though, that the Bank of International Settlements came out and said

this first. So, Poloz is not really saying anything new within a global context. But in Canada, this is not common knowledge.

So, shall we make it common knowledge via me explaining it to you. Simply put,

interest rates follow the economy, not the other way around. If you spend lots of time reading news, watching CBC, Bloomberg, CNBC, etc., then you have probably been exposed to a different argument. Most folks on those channels will tell you that, by lowering interest rates, central banks through monetary policy "stimulate" the economy. Lower rates mean lower borrowing costs, so people take on more debt, and boom - more economic growth! But, it doesn't work that way.

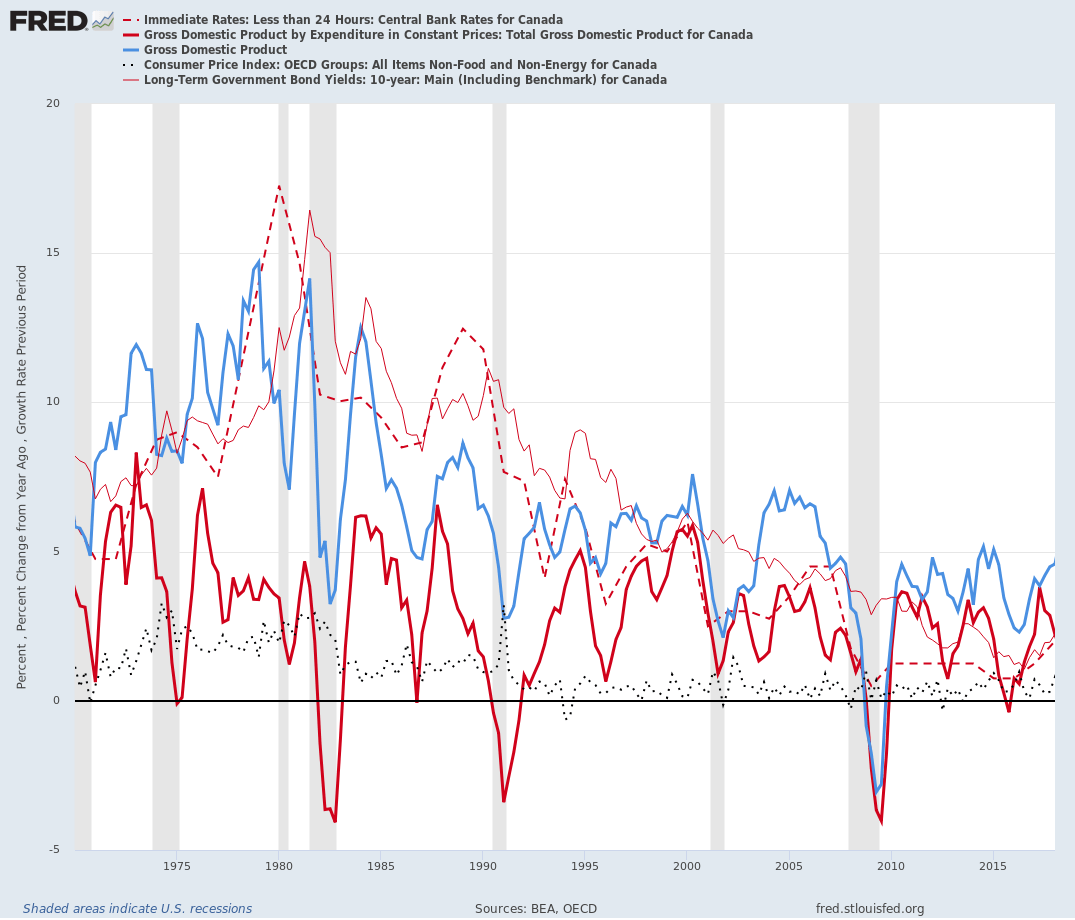

If you take a look at the chart below, you will see 5 variables (items) lined-up against one another. The red and black lines are Canadian data, while the blue and grey-shaded are the US data. Focus on the thick red line (nominal GDP), and the dashed red line (BoC interest rate).

What do we see? We see a tremendous lag between interest rate moves and growth. It's crystal clear. Importantly, we see a declining trend in both growth and interest rates. If lowering interest rates stimulated the economy, we would see an inverse relationship. Instead, we have a lagging pattern with growth leading the way. The thin red line (10-year Canadian bond yields) follows a similar pattern to the BoC's rate.

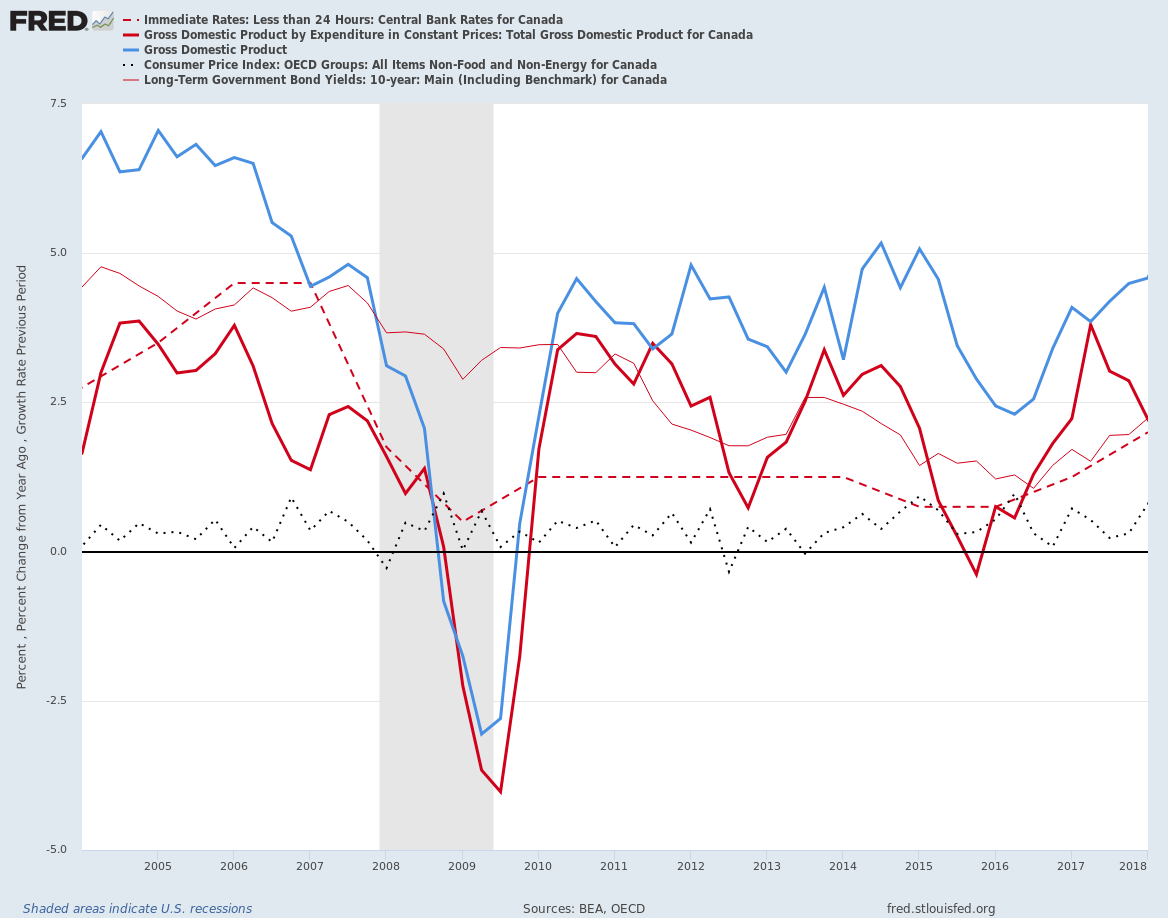

We can zoom-in a bit closer, as well. Below you have the same chart, but with a smaller time frame. You can see how the yields (interest rates) ebb and flow alongside economic growth. By 2005, economic growth was heading down, but interest rates were still trending up (especially the bank rate). Only after consecutively poor GDP performances, did the BoC lower the rate, with the market then following.

I've repeated this FACT about interest rates over and over again on this website, and I'll continue to hammer away at it until the entire country understands this perspective. I'll certainly be ok if you don't buy it, but I want you to consider it as an alternative and acknowledge that it has some robust logic and data behind it.

It makes sense when you attach a business example to it: when the economy is doing good people will pay retail on a pair of pants (so you can increase the cost of the pants if you're the seller). When the economy is doing poorly, people must cut back on spending and find deals (as the seller, you gotta discount the pants or they won't sell). The same thing happens in money markets. Rates on currency go up when economic growth is doing well.

What's important to note here, is that the cost of the pants (money) is secondary to accessing them - that is, being able to buy them. In advanced economies, we are used to having everything available to us with very few shortages in the supply chain. Unfortunately, this has distorted our sense of reality and understanding about how things actually work. Having access to buying pants (or money) is much more consequential than the cost of the pants (or money). If a bank does not

have a program or lending service for you, guess what? You won't be able to get the credit. At that point, it doesn't matter how much the credit costs.

Right now we have two problems facing the Canadian economy: 1) access to credit issues; and 2) interest rates at near-zero have not stimulated the economy.

Problem #1 to get an idea about how access to credit impacts the price or growth of something, just look at real estate. As I've covered, lower mortgage originations (due to a cut-off of access to home buyers) have negatively impacted price and volume of sales. Access to credit issues are diverse now, as well, due to the liberalization of banking in Canada and around the world. The history of banking shows us that banking shouldn't be a private enterprise. Out of any organizations in society, banks should be the ones that coordinate with governments the

most. They depend on government to survive a crisis, and they depend on the government's citizens to buy their product (fountain pen money). Once banks go out on their own, they try to maximize profits. Guess who their best clients are? The rich. Poor people don't pay good on money. And in many cases, they fail to pay entirely. So the banks focus their energy on extracting max profits out of the folks who pay. They also lend for the things that drive a return, rather than lend for things that fall in price and then depend on the borrower's wage to be paid back. Things that grow in value make for better collateral. Homes are a good example. Cars and electronics are terrible; you see the patterns, here?

Problem #2 exists because interest rates don't stimulate the economy. Interest rates just reflect the cost of the product. In this case, money. You can't sell it at a higher cost if folks can't access it (either willingly or unwillingly)!

You see, when economic growth deteriorates, or there is a good prospect to anticipate deterioration, stocks should follow. Why? Because poor economic growth means productivity and profitability decline (discount the stock as its not gonna sell at a higher price!). But I guess when you have a stock market with insane valuations (think Beyond Meat, with profits in the 20-40 million, but stock valuation in the BILLIONS), price-to-equity ratios and all of the traditional technical indicators go out the window. Investors and their creditors (the banks) are just chasing yield. So leave them alone, right?

We probably won't be saying that after a crash when short sellers have a field day, and when taxpayers are being held hostage by the banks for bailouts after decades of lending for speculative purposes, rather than engaging in economic development as they should be. Who will ultimately be responsible? The governments who let them get away with it...

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

Enjoyed this article and want to support our work, but are using an ad blocker? Consider disabling your ad blocker for this website and/or tip a few satoshi to the address below. Your support is greatly appreciated.

BTC Address: 13XtSgQmU633rJsN1gtMBkvDFLCEBnimJX